Personal Appeal

Listen to Molly discuss the process and purpose of Personal Appeal on this episode of the gallery’s podcast.

According to estimates by Acxiom, the largest consumer data collector in the US, the company holds an average of 1500 data points on more than 700 million people. Acxiom alone has more personal data collected on each American than the NSA, and for Americans born in the mid-80s and beyond, consumer data collectors began gathering information about them from the moment they were born.

Privacy and security are immediate concerns that come up in any conversation about Big Data, but for this project my interest is in the influences these practices have on our relationships to each other, and the impact they have on our fundamental needs for intimacy, understanding and belonging.

Our world is flush with technologies meant to bring our identities more sharply into focus and make us more known to each other (and to marketers.) Sophisticated Big Data gathering and analysis techniques are working to take the mystery out of who we are so that we can be known, understood, catered to, and relied upon as consumers. But there’s a difference between an accumulation of personal data points and the feeling of being known.

With these issues in the background, more than ever we need art that de-collapses us, that makes us more known to each other as unique, complex and contradictory, and recasts our psychological ambiguities, personal narratives of loss and joy, and constantly shifting, growing, changing, moving selves as a critical part of being and feeling known. We need art that reintroduces us to ourselves as unknown and unknowable, and therefore full of possible futures, not doomed to definition by our facebook feeds or credit scores.

In December 2014 I rented an Acxiom list of 10,000 names and addresses, to which I sent a generic marketing mailing asking for participation in a free art project. Seventy people responded to my invitation. From December 2014 – March 2015, I corresponded with them by email and mail, leading up to an in-depth questionnaire that asked participants to reveal their thoughts about death, regret, love and friendship. Their answers revealed other demographic information, including age, gender, marital status, home ownership, occupation, leisure interests and a host of other nuances.

My attempt to employ these marketing technologies to piece together the personal narratives of these participants is meant to show the empty space between being known as a collection of data points and feeling known as a person. But my aim is to illuminate and question, not reproduce the effect of Big Data, and so instead of presenting these 70 participants as subjects through public disclosure of their profiles, I worked with a web developer to create a performance interaction that would reveal these participants through their connections to gallery visitors. In the world of my project you have to give a little data to get a little data.

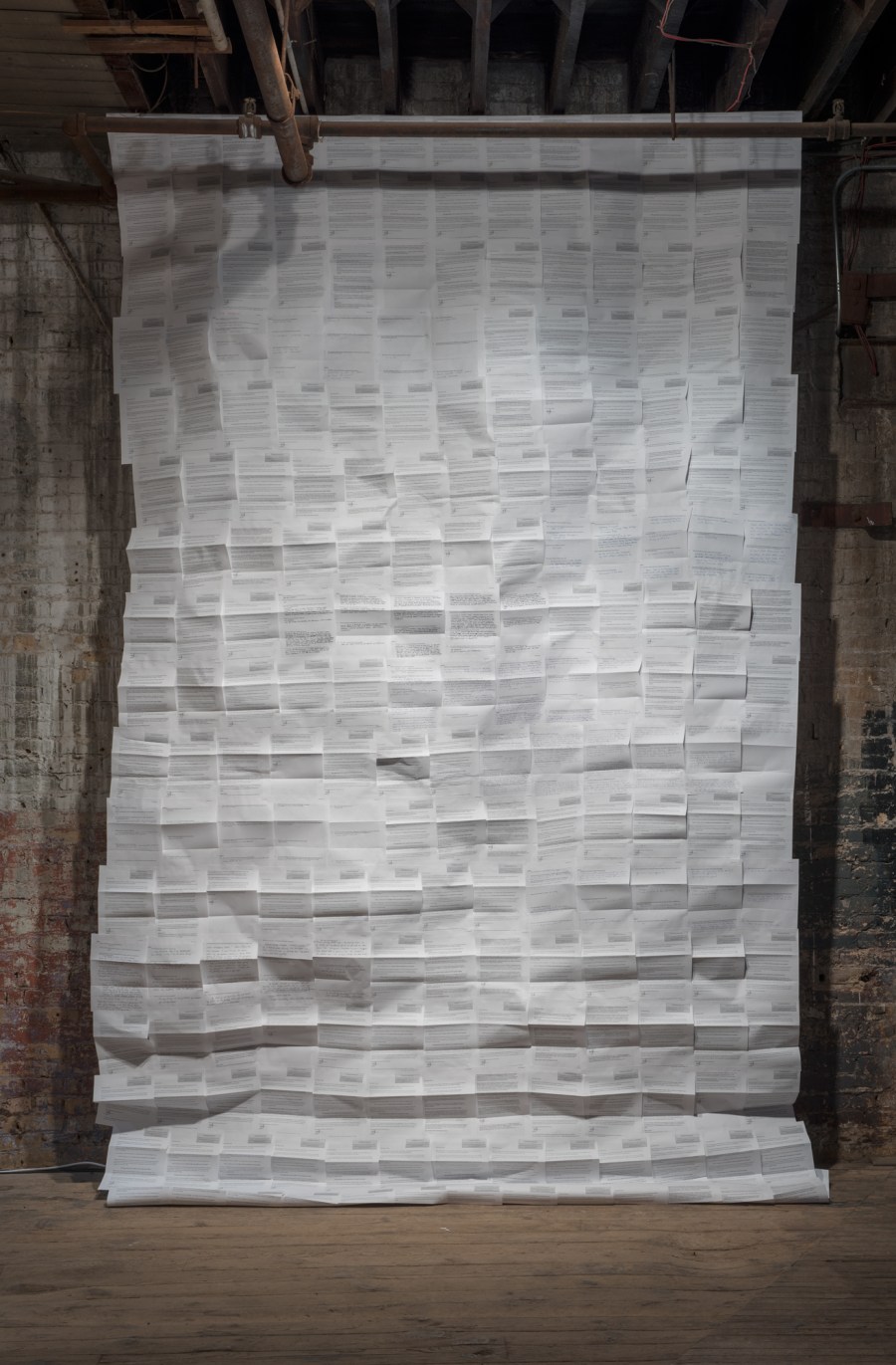

In the gallery installation, participants enter an area with towering letter collages and a small stage. They complete a short version of the original questionnaire through the online project app, and their answers are run through a data analysis API that analyzes such things as emotional tone and keywords. Based on their scores, text is retrieved from the project’s database of responses and populates a script created just for them. Finally, the pair of participants reads their scripts together over microphones, creating the effect of hearing their own emotional tone and attitude through someone else’s words, in their voice, thrown to another part of the room by a hidden speaker.

Heatmap collage of direct marketing participants in Personal Appeal, January 2015

Heatmap collage of direct marketing participants in Personal Appeal, January 2015